Earlier this year, Play Network Studios announced their latest project, Hijack 93’, a retelling of the Nigerian Airways Flight 9805 hijacking. Of course, it was met with a plethora of reactions, sparking conversations about Nollywood’s evolving storytelling approach. Now, the conversation extends beyond Play Network’s decision to tackle a story rooted in political history rather than pop culture nostalgia. Every decision in what I’d call the third wave of Nollywood feels pivotal because films have taken a somewhat bold shift—one where Nollywood is embracing its identity by revisiting stories that define us rather than retelling Western tropes.

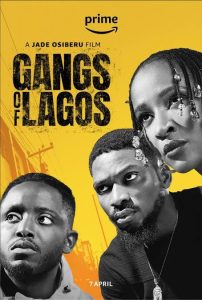

Recent hits like King of Boys and Gangs of Lagos reflect a growing appetite for narratives that thoroughly cover Nigeria’s socio-political landscape, folklore, and urban struggles. These films draw from our lived realities—stories of power, survival, and community—eschewing the Eurocentric perspectives that dominated Nollywood’s earlier years. Unlike generic rom-coms with Manhattan-style aesthetics, today’s Nollywood takes pride in showcasing our streets, our dialects, and our complexities.

To appreciate this evolution, we must trace Nollywood’s journey. Films were made in Nigeria pre-independence; for instance, the first films shown in Nigerian theatres were Western films, beginning in 1903. In 1926, Palaver, Nigeria’s first feature film shot in British Nigeria, was significant for its use of non-professional local Nigerians as actors. Post-independence, however, saw the film industry producing shots on celluloid by Nigerian filmmakers. This birthed our beloved home video boom era in the 1990s and early 2000s. It was the era of storylines focusing extensively on ‘village love,’ ‘tales of betrayal,’ and perhaps its most iconic milestone: Chris Obi Rapu’s Living in Bondage (1992).

While the ’90s were raw and defining, Nollywood began shifting toward a more glossy, Western-influenced aesthetic by the early 2000s, seeking international appeal. For example, Keeping Faith (2002), directed by Steve Gukas, featured a mix of romance, drama, and urban sophistication, deviating from the village-based or spiritual storylines dominating the 1990s. Similarly, Shirley Frimpong-Manso’s The Perfect Picture (though Ghanaian, heavily influenced Nollywood) leaned into aspirational aesthetics and Hollywood-mirrored themes, catering to a middle-class and international audience.

These productions marked a pivot toward glossy, Westernized storytelling. Characters were depicted in upscale homes, corporate offices, and luxury cars, emphasizing global appeal over grassroots authenticity.

Fast-forward to the digital streaming age, and we’re witnessing a “New Wave,” where directors like Kemi Adetiba and Jade Osiberu champion a blend of authenticity and modernity.

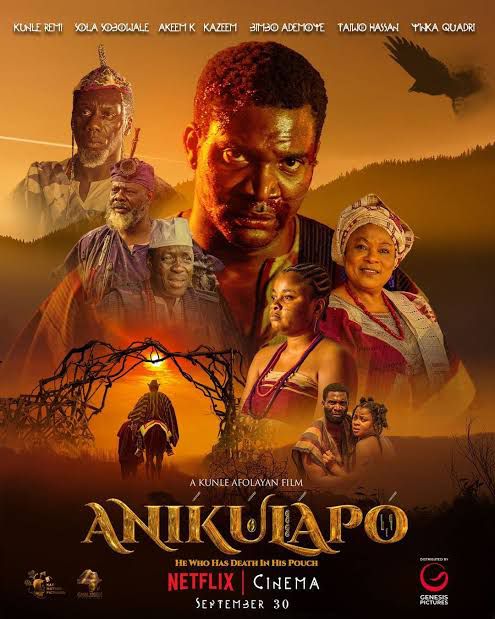

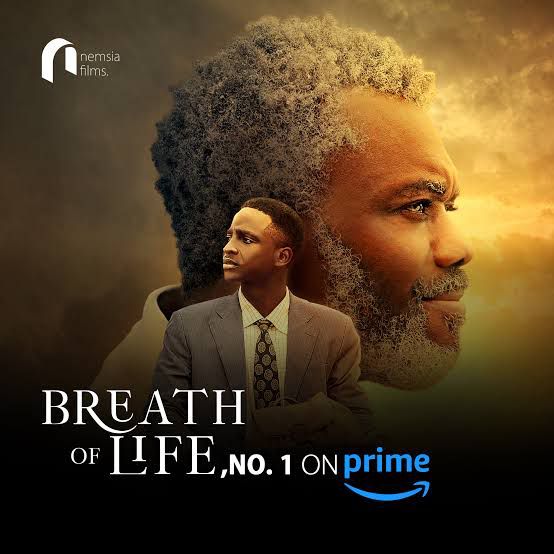

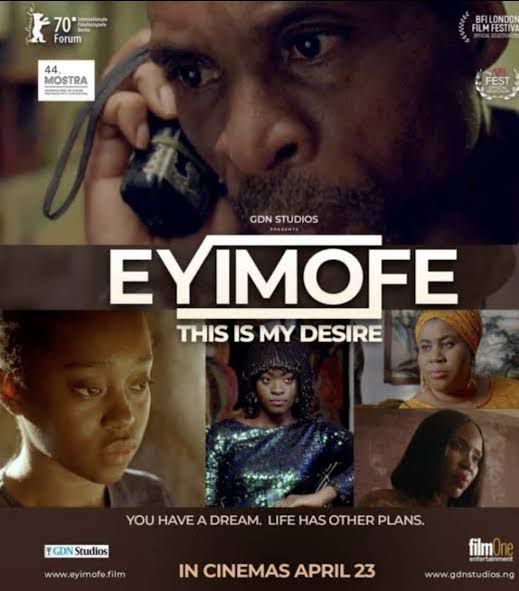

Despite its occasional stumbles, there is an obvious willingness to experiment, evidenced by the rise in genres such as horror. Films like Juju Stories (2021), Listen (2020), and Olumense’s Koi-Koi (2021) demonstrate this experimentation, exploring storytelling in ways that challenge traditional Nollywood norms. Impressively, the technical quality has also seen remarkable improvement. From sharp cinematography to immersive sound design, Nollywood’s growth demonstrates that it can deliver films with the production values required to compete globally. This is evident in visually stunning works such as Eyimofe (2020), Anikulapo (2022), Oloturé (2019), and Breath of Life (2023), which showcase the industry’s increasing focus on excellence.

However, even as Nollywood embraces a more nuanced approach, it raises the question: Have we truly mastered the art of telling our stories?

One recurring issue is the over-reliance on familiar tropes to signify “Nigerian-ness.” Take, for instance, the Lekki-Ikoyi Link Bridge, which has become almost synonymous with urban Nollywood. It’s featured in countless films as a marker of location, so much so that it feels like a character in itself. While it’s understandable that filmmakers might use the bridge to ground the story in a recognizable setting, its frequent and often unnecessary appearances can feel repetitive, especially when there are so many other landmarks and visuals that could better showcase the richness of Nigerian life.

.

While Nollywood strives for authenticity, it sometimes overcompensates, adding unnecessary subplots or forced “Nigerian elements” that detract from the main story. Take Vanity, where their nanny’s random fetishism felt bizarre, unrelated, and unnecessary—a weak attempt to salvage a storyline that had already lost its steam. They’re not alone. Other movies rely on underdeveloped dialogue in a bid to appear more Nigerian. The result? Films that are forgettable, underwhelming, and tiring—rising and falling on themselves before even reaching their climax. It is tortuous because such elements, while sometimes culturally relevant, feel forced and disrupt the main plot.

Moreover, some filmmakers dilute the essence of Nigerian culture in pursuit of international appeal. The challenge is finding the balance: how to create films that resonate locally while remaining accessible to a global audience. This is where the question arises: Who are these stories really for? As Nollywood increasingly caters to international markets, many Nigerians find themselves struggling to relate to what they see on-screen.

There’s also a troubling lack of attention to detail. Nigerians have such unique and diverse experiences that Nollywood should have an endless reservoir of stories to pull from. Yet, we continue to see a narrow focus on urban-centric narratives, or worse, lazy, underdeveloped ones

Could this hesitance stem from a fear of confronting more complex or controversial subjects? Stories like Hijack 93’ tap into historical and cultural moments that demand vulnerability, yet the execution falls short. Inconsistencies in costume design and story structure manage to make a film about a hijacking—its central plot—feel like a side plot.

Or take The Origin of Madam Koi-Koi, an adaptation of the Nigerian urban legend featuring a vengeful ghost who haunts dormitories, hallways, and toilets in boarding schools at night. The film provides a backstory explaining why she haunts, but it leaves the viewer questioning whether the theme of sexual violence is merely a plot device created for one thing only—trigger the viewers. Nothing is addressed clearly, and by the end, it leaves viewers confused about its overall point. Are filmmakers avoiding more controversial or nuanced narratives because they’re too risky? Stories of political corruption, tribal conflicts, or diaspora realities remain underexplored, despite their potential resonance.

Authenticity should enrich storytelling, not constrain it. While some films manage to strike this delicate balance, others falter under the weight of trying too hard to be ‘authentic.’ The key lies in variety: embracing experimental genres, critical perspectives, fresh settings, and untold narratives that can broaden Nollywood’s storytelling scope.

As the industry evolves, the challenge is not just to tell stories, but to do so in ways that genuinely reflect our identity—crafted with care, nuance, and creativity. The question now is: are we ready to tell our stories in their rawest, truest forms, or will we continue to shy away from the complexities that define us?