Ghana’s music industry boasts a vibrant history marked by the evolution of diverse genres that continue to shape its cultural and creative identity. From the inception of the profound Highlife and Hiplife sounds to contemporary sounds like the famous Afrobeats and its functions to HipHop, Reggae/Roots, Dancehall and Drill, these genres have defined different eras, reflecting local traditions and global influences.

Nonetheless, like every industry in the new-age world, Ghana’s music industry witnessed some evolution within the space, marked by dynamic shifts in sound and the emergence of diverse music genres. And with every era, Ghanaian musicians have proven – time and again – why they are among the best creatives and innovators of music, contributing significantly to the continent’s music narrative.

However, the conversation surrounding genre development and sustainability within the industry remains critical, requiring an examination of its key challenges and opportunities. In the context of this piece, the writer wishes to indicate that this article derails from the agenda of rivalry but takes on origination and maintains a nuanced reflection of Ghana’s music space vis-a-vis global impact.

The Bedrock

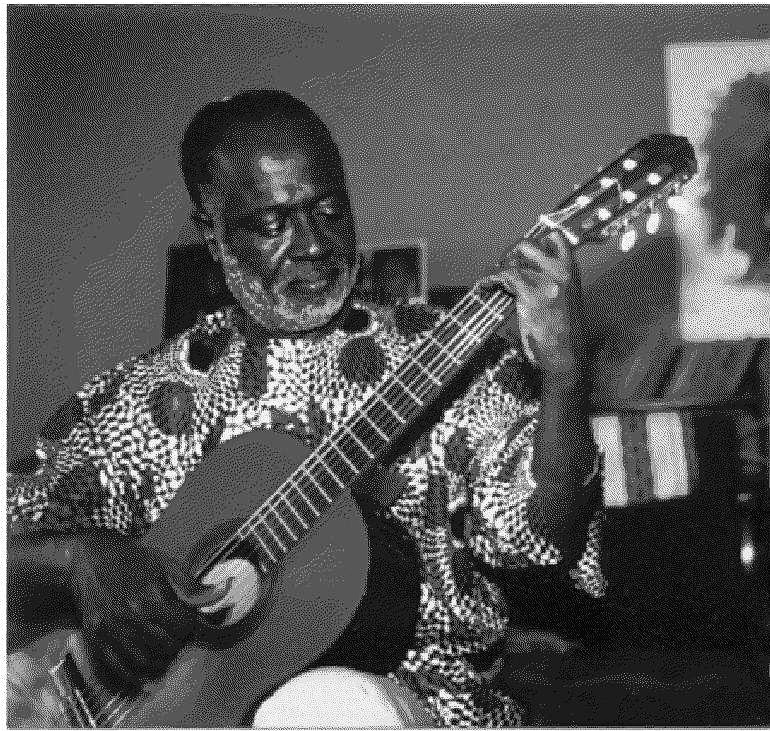

Emerging in the early 20th century, Highlife is arguably the cornerstone of Ghanaian music. Defined by its fusion of traditional rhythms with Western instruments and jazz elements, highlife became the soundtrack for introspective commentary, social gatherings and political movements. Pioneers like Nana Koo Nimo (King of Palm Wine highlife), the celebrated Osibisa band, made of Teddy Osei, Mac Tontoh and Sol Amarfio (all of blessed memory), as well as the late E.T. Mensah, who is often referred to as the “King of Highlife,” all played crucial roles in shaping the genre and popularising it across West Africa and the Diaspora. These names are just a few out of the industrious list the country has produced over the decades.

The fusion of the sounds created a sophisticated sound that continues to influence generations and reflect the times. This adaptability has remained a defining characteristic of Ghana’s music scene, leading to the birth of Hiplife in the 1990s. The genre married highlife’s melodic sensibilities with hip-hop’s urban energy. Again, while the famous Gyedu-Blay Ambolley is touted as one of the sound’s pioneers, Reggie Rockstone popularised the sound and coined the term “hiplife” in 1994. Like every invention, the genre has had disciples while transitioning.

Ghanaian artists have and are pioneering new sonic blocs. The space has seen the emergence of Azonto, what many idealised as Nshorna Music (to mean beach songs), Afrobeat -and its subs as Afropop, Afrofusion, Afro-soul, Afroswing, to Asaaka and the many varying alternatives (alté) and niche sounds.

While these eras have marked some defining and memorable moments in the country’s history – both locally and continental – Ghana as a country and an industry has largely failed to service our innovations. What do I MEAN?

Influence, Service & Disservice

While Ghana’s music industry has seen remarkable growth and genre diversification, the lack of documentation and obsession for rush trends have marred the sustainability and full potential of its influence, defeating the potential reach the country’s genres could accomplish despite the adverse effects of the political tensions in the region at the time. However, the responsibility to preserve and develop Ghanaian music lies with industry players. Their failure to establish a unified and structured industry framework has further stalled progress, making sustainability a pressing concern.

Conversations with key figures in the industry reveal that essential genres, particularly hip-hop and Azonto, were hastily disregarded, stunting their long-term impact. While highlife remains the foundation of Ghana’s musical heritage, hip-hop and Azonto stand out as some of its most influential exports.

People, particularly musicians and stakeholders, around the emergence of these genres didn’t fully catch on to the wave and influence of the genres. In an attempt to push for what was deemed “fresh,” the sound went through a slump – fast rise, fast fall and discarding. We again witnessed sub-genres like Raglife and Twipop, though with distinct names, did not offer the “fresher” wave the proponents anticipated. Although the approach and efforts were commendable, the result was largely insignificant and stalled the music environment.

It’s 2025, and although flaws exist like in every institution, the current landscape brews hope and grace. We’ve seen the revival of our heritage sounds, with new-age artists exploring, sampling, and blending iconic sounds with the fresh sounds of today.

Sustainability and the Way Forward

To ensure the continued development of these genres, several factors must be addressed, particularly;

Education:

One of the key pillars for sustaining Ghana’s music genres is education. This extends beyond just music institutions and formal training. Artists, producers, and industry stakeholders must prioritize knowledge transfer through formal and informal mediums. There is the need to cultivate a sense of ownership among young artists while eschewing the over-fixating on who started and brought what to the mainstream. We can’t stress the essence of this enough but music education should be embedded in school curriculums like it was in the 90s and early 2000s.

Documentation:

A well-documented industry is critical to the preservation of culture. It defines, tracks and amplifies the growth and preserves the history of a people, in this case the music industry. Unfortunately, one of the major gaps in Ghana’s music industry is the lack of deliberately structured documentation by academics, cultural writers and archivists. Many genres and sub-genres fade away because there is no clear archival reference. Without proper records, the industry struggles with continuity. Documenting Ghana’s music journey ensures that future generations have a blueprint to follow and can easily trace their musical roots.

Identifiable Industry:

For Ghanaian music genres to thrive, there must be an identifiable industry structure that functions effectively. A fragmented industry makes it difficult for any genre to sustain its impact. Key industry bodies must focus on creating a regulatory framework that ensures proper revenue channels, publishing rights, and fair representation of Ghanaian sounds.

The future sustainability of these genres will depend on continued innovation, strong industry infrastructure, and the ability to connect with new audiences while maintaining cultural relevance. As technology and cultural practices continue to evolve, Ghana’s music genres will likely continue to adapt and thrive, contributing to the immense diversity of African music.